Nobel laureate fought the odds to make history

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Latest news Topic

- Erika Martin Author

By Erika Martin Friday, October 10th, 2014

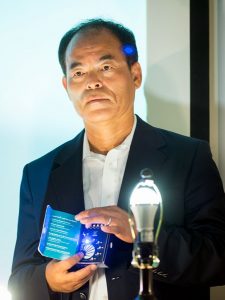

Nobel laureate Shuji Nakamura displays the genesis of his invention, the blue LED, at a press conference Tuesday, Oct. 7 on the UCSB campus. (Nik Blaskovich / Business Times photo)

Thomas Edison had plenty of help when he invented the first commercially viable light bulb more than 125 years ago.

UC Santa Barbara professor Shuji Nakamura, by contrast, was working virtually alone at an obscure Japanese company with a minuscule research budget when he first developed the blue light-emitting diode, or blue LED.

In the relatively short time since his 1992 discovery, Nakamura’s LED technology has supplanted Edison’s incandescent bulb. And Edison never became a Nobel laureate.

Nakamura and two scientists based in Japan, Hiroshi Amano and Isamu Akasaki, were chosen as recipients of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics this week.

Although red and green LEDs had been in existence since the 1960s, the discovery of shorter-wavelength blue LED was a technologically difficult feat that allowed consumer devices to read and write more detailed bits of information.

Today, the LEDs and lasers form the foundation of an array of modern consumer electronics, such as Blu-ray players and the Playstation.

The committee selected the team for its invention of the blue light-emitting diode, or LED, which allows white light to be created in a manner that is both energy-efficient and visually similar enough to incandescent bulbs to attract wide consumer appeal.

Nakamura holds more than 100 patents and has published more than 400 research papers. He is the sixth faculty member at the university to win the Nobel Prize since 1998.

Speaking at a press conference, Nakamura said he was asleep when he received the Nobel panel’s call, “but then I was nervous, so certain parts of me were sleeping and certain part of me were waiting to see.”

He will share the $1.1 million award with Akasaki and Amano, the Japanese researchers, who worked together to discover blue LED technology at Nagoya University simultaneously with Nakamura, who was working alone at Nichia Chemical Corp.

Nakamura, 60, was born on an island in southern Japan. An interest in science naturally accompanied his curious mind and love for the outdoors, and as a child he spent every day on the beach with his friends. But his hometown was so small, and its economy so centered on fishing and agriculture, that it did not have a high school.

Had Nakamura’s family not moved to a larger city when he was in second grade, his education might have been terminated early.

He later attended the University of Tokushima and graduated in 1977 with a degree in electrical engineering. He was hired as an engineer at Nichia. The company’s specialty at the time was fluorescent lights. When Nakamura asked if he could make green and blue LEDs immediately after being hired, the company’s chairman told him he was crazy, and there was not enough money to fund the research anyhow.

Such tense exchanges characterized Nakamura’s relationship with his employer, who didn’t allow the researcher as much creative leeway as he would have liked. “When I was in Japan, my incentive to work very hard was anger,” he said. “Without anger, I couldn’t have done anything.”

Nakamura hoped to research in the U.S., but had only ever received the equivalent of a master’s degree. While he was working as a visiting researcher at the University of Florida, he realized how important a Ph.D. would be for that goal. “I came back to Japan and my dream was to get a Ph.D., not to develop the blue LED,” he said.

Nakamura earned what is known in the county as a paper degree, a sort of do-it-yourself doctorate awarded to researchers who publish five research papers.

Now a U.S. citizen, he left his home country to join the UCSB faculty in 2000, after taking an unconventional route to the world of academia.

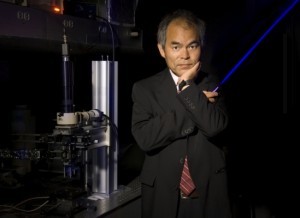

Shuji Nakamura became UC Santa Barbara’s sixth Nobel Prize winner for the invention of the blue LED. (photo courtesy of UCSB)

Nakamura has pioneered many scientific developments since joining UCSB’s Materials and Electrical and Computer Engineering departments in 2000. He is recognized for his advancement of semiconducting technology using gallium nitrides and world-renown as a pioneer in light emitters.

While the Nobel Prize winners are chosen in recognition of being the first to discover a technology, the honor is just as heavily weighted by humanitarian impact. Nakamura’s pioneering work expanded impoverished populations’ access to light and livelihood. Although 1.4 billion of the world’s people lack access to electricity, solar-powered LEDs allow these communities to spend money on food instead of fuel.

“This technology is very popular in developing countries,” Nakamura said. “Also, the cost is very cheap, because without white LEDs it means they have to buy oil — it’s very expensive. But with the solar-cell, processed-battery LED, the initial investment is $10 or $20 and there are no more costs.”

“When you think that the LED, that Shuji and colleagues invented, is 20 times more efficient than the incandescent light-bulb, and when you realize that 25 percent of the energy expended in the world is in lighting, you see the enormous impact, both economically, in terms of cost-savings, and as importantly from a society point-of-view, in terms of good stewardship of very, very precious resources,” said Rod Alferness, dean of the school’s College of Engineering.

UCSB Chancellor Henry Yang, who was in Hawaii for the groundbreaking of the 30 meter space telescope when he got news of the campus’ honor, issued a statement congratulating Nakamura.

In the letter, Yang shared a story about fellow Nobel laureate in physics and UCSB professor Herbert Kroemer, who described the first time he saw a bright blue LED.

“What we are seeing here is the beginning of the end of the light bulb,” Kroemer said, according to Yang. “We are not just talking about doing things better, but about doing things we never could before.”

Nakamura is also the co-director of the campus’s Solid State Lighting & Energy Electronics Center, where a great deal of work has gone on since Kroemer first saw that burst of blue light. “Ever since Shuji’s invention of the blue light-emitting diode and energy-efficient white LED, he and our colleagues have been pioneers not only of a new field of research, but of a scientific revolution,” Yang wrote in his statement.

“I think Shuji indeed felt constrained when he was working for Nichia, and coming to an academic position has given him a lot more freedom to pursue the research agenda that he considers most relevant,” Professor Chris Van de Walle said. “I also think he chose well to come to UCSB, which is famous for its collaborative environment.”

Nakamura’s groundbreaking and transformative research epitomizes the interdisciplinary efforts that make the university’s College of Engineering such a vibrant and successful program. The campus is home to probably the largest academic research effort in nitride semiconductors in the world, Van de Walle said, which in turn has attracted a lot of industrial research funding.

“The achievements of Shuji Nakamura, and other nitride experts such as professors Jim Speck, Steve DenBaars and Umesh Mishra, attract worldwide attention and help us recruit the best and brightest graduate students and postdocs,” Van de Walle said. “For myself, when I joined UCSB 10 years ago after spending almost 20 years in industrial research labs, Shuji’s and UCSB’s leadership in nitrides was a major attraction.”

The widespread applicability of the technology was easily apparent, and in 2001 Nakamura filed a suit against Nichia Corp. for paying him the equivalent of $180 for the patent in the early 1990s.

The Tokyo District Court ruled in 2004 that Nichia could have earned more than $1.1 billion in profits from blue LEDs since they appeared on the market and ordered Nichia to pay Nakamura $180 million in compensation.