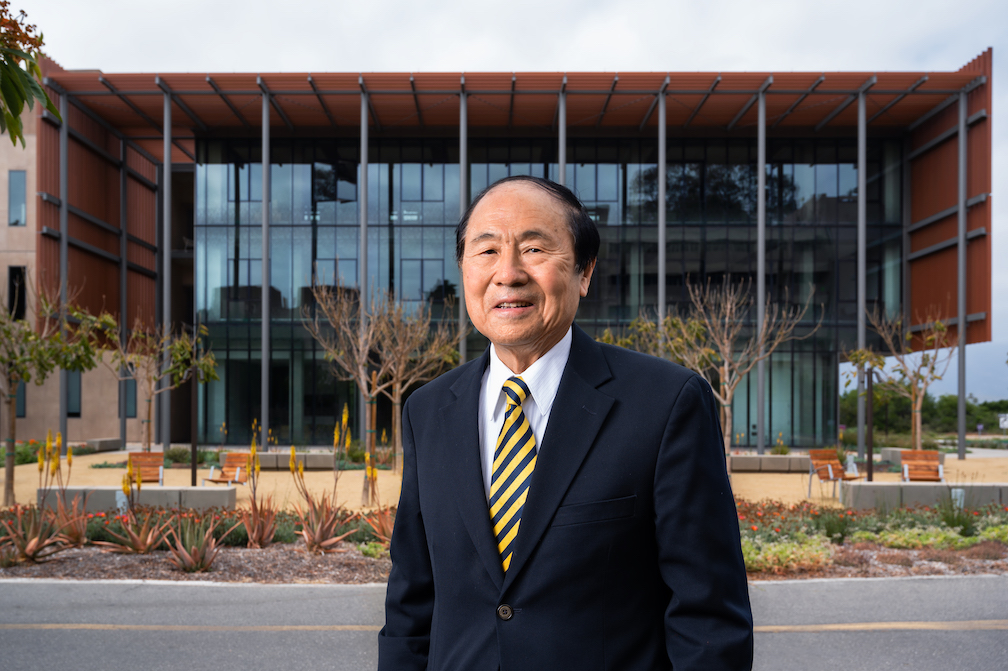

Business Times Hall of Fame: UCSB Chancellor Henry Yang

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Higher Education Topic

- Tony Biasotti Author

By Tony Biasotti Friday, April 23rd, 2021

Editor’s note: Henry Yang, the chancellor of UC Santa Barbara since 1994, is this year’s entry into the Pacific Coast Business Times tri-county business Hall of Fame. He will be honored in a virtual event on May 20. Register for the event here and check out the entire Hall of Fame special section here.

He’s never started a company or worked as a corporate executive, but Henry Yang might be one of the greatest job creators in the region’s history.

When Yang arrived in 1994 as chancellor, University of California, Santa Barbara was a different place. It was less prestigious and selective — back then it admitted about 85% of its undergraduate applicants, a figure that is now around 27%, and it had yet to assume its current position as one of the highest ranked public universities in the nation. It was less ethnically diverse than it is today. Its campus was still dominated by mid-century concrete-block buildings. Its faculty had just one Nobel laureate, who won the prize before he came to UCSB.

And the university only occasionally produced any successful “spinout companies” — ventures founded by students, staff or faculty, or a technology or tech-based idea developed within the university.

Now between four and six startups a year are spun out of the university, and it has hosted six Nobel Prize winners since 1998. Those 115-plus spinout companies — among them, InTouch Health, Inogen and Apeel Sciences — have raised billions of dollars in public and private funding and employ thousands of people on the South Coast and around the world. When combined with UCSB’s own 4,250 employees and $1.3 billion in annual economic impact, those companies form the backbone of the Santa Barbara region’s economy and have made the South Coast one of the nation’s best environments for startups.

“UC Santa Barbara is a magnet for innovation,” Yang said in an email interview with the Business Times. “Our magnetic field is growing stronger all the time.”

The one constant through those 27 years of change has been Yang. Now 80, he is the longest serving chancellor in UCSB’s history, the longest serving in the UC system, and one of the longest serving current chief executives of any major public research university in the country.

“The university really blossomed into one of the great public research universities in the country,” said Michael Witherell, a professor at UCSB from 1981 to 1999, and Yang’s vice chancellor for research from 2005 to 2016. “It developed continuously over time, but by far most of that development has been under Yang’s leadership.”

An engineering professor turned administrator, Yang still teaches undergraduate classes, advises graduate students and publishes papers in academic journals. He and his wife Dilling live on campus, and, when there isn’t a pandemic, they eat in the student dining halls and can often be seen walking around campus or the neighboring town of Isla Vista, chatting with students and posing for selfies.

“It’s common for university presidents and chancellors to last about eight or nine years,” said Witherell, who is now the director of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “These are really difficult, demanding jobs, and I think it takes a certain kind of person who can get into the rhythm of dealing with that demanding, difficult job as a marathon and not a sprint, and that’s a particular strength that Henry Yang has.”

Yang was born in Chongqing, China in 1940, and moved with his family to Taiwan in 1949. As a child, he always had “a deep interest and fascination with aircraft,” he said, and that led him to study engineering. He studied civil engineering at National Taiwan University and then came to the United States to get his master’s degree from West Virginia University and his doctorate from Cornell University, both in structural engineering.

“Making the decision to study in another country requires a willingness to step outside one’s comfort zone,” Yang said. “I guess you could call it a spirit of adventure! It’s like a balloon you have always lived in suddenly pops. There will certainly be challenges, but also, I think — and I’m speaking from experience here — great rewards.”

Yang joined the faculty of Purdue University in 1969, and by 1984 he was the dean of the university’s college of engineering.

That set the stage for his move to UCSB. The UC Regents hired him as UCSB’s fifth chancellor in 1994.

He soon began to put his stamp on the university and its relationship to the region’s business community. When Yang arrived, plans were already in the works for what would be known as the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management. The graduate program’s first faculty were hired in Yang’s first year at UCSB, and in 1996 the first master’s students were admitted, followed by doctoral students in 2000.

In the late 1990s, the College of Engineering started a business plan and mentoring program. In 2004, it became a graduate certificate program known as the Technology Management the program, which now grants both master’s and doctorate degrees in technology management.

Under Yang’s direction, UCSB has remade how it handles the patents developed on campus by faculty and students.

That intellectual property belongs to the UC system — or, technically, to the system’s governing board, the UC Regents. When Yang arrived at UCSB, the UC Office of the President in Oakland managed UCSB’s intellectual property. In 1999, Yang hired Sherylle Mills Englander, and in 2005 she became the director of the UCSB Office of Technology & Industry Alliances, which began to manage intellectual property developed at UCSB and license it to businesses that want to use the university’s innovations.

“Chancellor Yang was very involved in the decision to form this office,” Mills Englander said. “It made complete sense, but it wasn’t without risk. … You’re filing patents to protect things you think are important and valuable commercially, but not everything finds a commercial home and the patent costs are the same regardless.”

Obtaining a patent can cost between $20,000 and $45,000. At first, the office ran a deficit, but now it returns “a modest revenue to the university,” Englander said, which goes back into funding research.

UCSB now averages around 90 invention disclosures per year and has more than 650 active inventions, 500 U.S. patents and 150 active license agreements.

Sometimes, the company that licenses a technology has no other connection to UCSB, while in other cases, the researcher who made the discoveries starts a company based on the innovation. In the latter case, UCSB now offers all kinds of support that didn’t exist early in Yang’s tenure, including an on-campus business incubator with a wet lab and prototyping facilities.

“As a public research university, the goal of our teaching, research, and scholarship is to create and transfer knowledge that advances the well-being of our state, nation, and globe,” Yang said. “By moving groundbreaking research and discovery from campus to the marketplace, we are helping to address some of today’s biggest challenges and to build a vibrant and diverse economy.”

Innovation at UCSB didn’t start under Yang. The ecosystem of spinout companies dates at least back to 1987, when Physics Professor Virgil Elings founded Digital Instruments to commercialize his research in scanning probe microscopes.

But the pace of innovation under Yang has skyrocketed, and enough companies have come out of UCSB to create an ecosystem in the Santa Barbara area of entrepreneurs, skilled workers and venture capital. In fact, a 2015 study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ranked Goleta as the best place in California for startups, outside of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Peter Rupert, a UCSB economics professor and the director of the UCSB Economic Forecast Project, said Yang’s role has been to create a culture in which entrepreneurs can thrive. He’s done that in a collaborative way, while honoring and even expanding the role of faculty in the university’s governance.

“It’s not a top-down environment,” Rupert said. “He’s very accommodating and he listens to people. When someone has an issue for the chancellor, he allows them in, he talks to them, and then he makes really great decisions at the end of the day.”

Yang has been a successful fundraiser and has overseen a gradual physical rebuild of the campus, with new science buildings, a new classroom building and a completely renovated library.

He has also deftly navigated the political terrain that comes with being chancellor. When problems arise — for example, the environmental and public safety impacts of the spring beach party that started as Floatopia in 2004 and of the annual Halloween parties that go back decades farther — UCSB has worked with local government and law enforcement and often provided concerts and other alternatives for students. The result is a campus that with a reputation for both fun and academic rigor.

Yang has also had two tragic opportunities to act as UCSB’s consoler-in-chief. In 2001 and again 2014, multiple UCSB students and other residents were murdered in Isla Vista.

“The only way to navigate such dark days is to come together, as a community, as a family,” Yang said. “In doing so, our campus emerged with a renewed sense of strength, resilience, and unity—qualities that have helped us face the more recent challenges of fire, flood and pandemic.”

A common refrain among people who graduated from UCSB before the Yang era, or early in his tenure, often express sentiments like “I’m glad I got in when I did because I’d never get admitted today,” or, “my degree is worth a lot more because the school is so much better now.”

Salud Carbajal, who has represented the Santa Barbara area in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2016, is one of those alumni. He graduated from UCSB in 1990, when it was, in his words, “a good school.” Now, he said, it’s “an extraordinarily great school,” and the key figure in that transformation is Henry Yang.

“The status of the university today, the prestige it has gained, is due in great part to his longevity and his skills and his talent,” Carbajal said. “Chancellor Yang comes across as low-key but that should in no way mischaracterize the enormity of his talent and his passion for improving the university. In his quiet way, he has achieved so much, without fanfare and grandstanding. … Henry Yang and the university are a powerhouse for our community.”